Author Archive

3 Benefits of Supplementing Horses with Magnesium

Editors note: This article has been sourced from Riva’s Remedies.

Magnesium is a very well-known mineral and is used by millions of people for its health benefits. Magnesium is required for the normal function of every cell in the body and is necessary for muscle and joint health, metabolism, energy levels, and a healthy nervous system. It is therefore an extraordinary mineral for horses since our horses need a lot of support for both their muscle function and their stress levels.

And, since grass and hay does not usually provide enough magnesium to meet their daily requirements horses often exhibit signs of deficiency such as irritability, muscle tension, muscle fatigue, spasms, nerve pain, and Insulin Resistance.

But even though magnesium deficiencies are common, your equine partner doesn’t need to be deficient to benefit from the numerous benefits of magnesium. Like all minerals, magnesium, when provided in therapeutic dosages, can help horses with a variety of different health conditions.

Let’s take a look at 3 of the most common uses of magnesium for horses:

1) Bone and muscle function

Sixty percent of tissue magnesium is located in the skeleton. It is essential for maintaining healthy bones by initiating the chemical pathway for calcium absorption. It helps to dissolve calcium in the blood for absorption into the tissues and bones. When magnesium levels are too low for a long time, it can lead to calcification of the bones and joints which can contribute to bone spurs, arthritis, and hoof pathologies.

While calcium is responsible for muscle contraction, magnesium is required for muscle relaxation. Deficiency signs include muscle spasms, cramping, fatigue and an irregular heartbeat. Magnesium can also be used therapeutically to alleviate muscle tightness, tension and spasms. As an anti-spasmodic, magnesium can also help relax the intestinal muscles during episodes of colic, both acute and chronic.

2) Conditions of the nervous system

Magnesium supports the nervous system by regulating neurotransmitters and facilitating nerve transmission. It is also heavily involved in managing the stress response by supporting healthy production of cortisol from the adrenal glands. Horses that are deficient in magnesium will often exhibit nervous behavior, anxiety, and a low threshold for stressful events. As a result, magnesium is commonly used as a natural relaxant for high strung or anxious horses during times of physical and emotional stress. It can even be used as a remedy for neurological conditions.

3) Sugar metabolism and energy production

Magnesium is also very important for carbohydrate or sugar metabolism. This can be especially beneficial for horses that are easy keepers or horses that are Insulin Resistant or have Cushing’s Syndrome (PPID). Magnesium plays a key role in converting glucose from feed to energy. If magnesium levels are depleted, the cells will be more resistant to insulin which is the hormone responsible for transporting glucose into the cells for energy.

Factors that can lead to magnesium deficiency in horses

- Insufficient levels in grass and hay

- Stress

- Diarrhea

- The use of diuretics

- Toxic heavy metals

Now that you know more about the signs of magnesium deficiency in horses, what type of magnesium should you use?

When choosing a magnesium supplement for your horse it is important to know which one is going to get the best results. There are many different types of supplements out there and no two are created the same.

Let’s explore your options…

Minerals are naturally derived from the earth and are essential to sustain every physiological function in the body – human and animal. All minerals, including magnesium, are classified as inorganic elements because of their chemical properties and position on the periodic table.

However, when supplementing magnesium as a dietary nutrient there are two types available for horses that you should be aware of: organic and inorganic.

Organic magnesium for horses

Organic magnesium is the most bioavailable form for horses.

Common organic forms of magnesium include:

- Magnesium citrate

- Magnesium gluconate

- Magnesium bisglycinate

These magnesium compounds are considered organic because the magnesium is chelated or attached to a carbon containing molecule. Bonds that contain carbon more closely resemble the natural compounds found in plants and other living things. This allows them to be more easily recognized by absorption sites and transported from the small intestine into the bloodstream.The rate of magnesium absorption depends on the group that is chelated to magnesium. Magnesium citrate has a reported absorption rate of approximately 30% which is higher than many inorganic forms.

Inorganic magnesium for horses

Inorganic magnesium is the most common form found in equine supplements and horse feed, but it is also the least bioavailable compared to organic forms.

The two most common types of inorganic magnesium are:

- Magnesium sulfate

- Magnesium oxide

Both of these magnesium compounds are classified as inorganic because they don’t contain carbon in their chemical structure. As a result, the body doesn’t recognize them as naturally occurring molecules such as those found in plants. Consequently, they aren’t broken down as easily into smaller units for transport across the intestinal lining into the bloodstream. Magnesium oxide, for example, has been reported to have an absorption rate as low as 4%.

It is also worth noting that dietary minerals compete for absorption. After inorganic molecules are broken down into positively or negatively charged ions, they are attracted to certain binding sites on the intestinal lining. Ions from other minerals with the same charge can often interfere and prevent other inorganic minerals ions from binding.

This is further evidence that your horse is possibly only absorbing a fraction of what they are getting in any commercial feed program. It also explains why many horses still show signs of nutrient deficiencies even though they are regularly supplemented with a mineral mix and a complete feed.

Organic forms of magnesium are always superior for horses…

It is estimated that up to 20% of all horses and over 50% of sick horses are deficient in magnesium! It is therefore important to select a high-quality organic form that is bioavailable and will deliver maximum benefit.

Unfortunately, when horse owners are looking for a magnesium supplement for their horses, they will often choose magnesium oxide because it is less expensive than the organic forms. The price difference is because the oxides don’t require the extra processing to chelate the magnesium with a carbon-containing group.

However, it is our that experience that not only do horses do better on the organic forms of magnesium, but most horse owners are always glad they chose a higher quality magnesium supplement to get the results their horse needs.

How much magnesium does your horse need?

Most horses respond well to 1,500 mg daily of magnesium citrate which is usually enough to correct most deficiencies and to provide relief from stress, tension, or muscle tightness.

However, when using magnesium to relieve acute pain, colic, or muscle spasms, a loading dose of 3,000 mg daily can be given for the first few days, or as needed for comfort. Once the horse responds, the dosage can be lowered to 1,500 mg daily.

In summary, if you suspect that your horse is deficient in magnesium or if you think that they might benefit from the many amazing properties of magnesium, make sure to supplement with an organic form to ensure high absorption.

And remember, you should never have to feed a supplement forever. A course of 4 – 6 weeks is plenty of time for your horse to demonstrate the benefits and then you can reduce to a maintenance dose as required or use as needed.

De-worming Your Horse: Using Chemicals and Herbs for Management and Prevention

Editor’s Note: This article has been sourced from Riva’s Remedies.

Why do Horses get Parasites?

Of all domestic livestock, horses have the largest numbers of parasites including large strongyles, small strongyles, roundworms, and pinworms. Roundworms only affect weanlings and yearlings, with encysted larvae migrating to the liver, heart, or lungs. Infected youngsters will generally show symptoms of malnutrition, colic, failure to thrive, unhealthy hair coat, pot belly, and possible coughing. Pinworms lay eggs around the anus of the horse, causing tail itching and hair loss. However, I find that most cases of tail itching in the summer time is actually due to the sugars in the grass.

Horses that graze on grass in a domesticated living environment are the most susceptible, since parasites spend a part of their life cycle living on the grass blades. In fact, studies have determined that grazing horses are far more likely to host parasites than those horses housed on dry lots with hay diets. Horses graze close to the ground and, more than other livestock, are always smelling, nibbling, and licking, whereby they can pick up large numbers of infective larvae.

Grazing horses are also at risk if they are allowed to overgraze their pasture, because overgrazed, nutrient-poor grass favours higher larval populations. Insufficient space for multiple horses is also a risk factor because in tight quarters they are more likely to pick up eggs shed by one another.

The Path of the Parasite?

Once in the horse’s digestive tract, female parasites lay eggs in the hindgut. In the spring, these eggs are passed to the ground inside the feces. Under proper environmental conditions, including warmth and moisture, the eggs hatch into larvae in the manure. But under cold and dry conditions, the eggs can survive un-hatched for long periods, waiting to emerge when the conditions are right. The infective larvae migrate onto grass blades, where they remain until grazing horses swallow them. They then develop into young parasites in the intestines.

Encysted Strongyles

Usually in the fall, prompted by the changes in daylight, ingested intestinal larvae penetrate the wall of the large intestine and begin another life cycle within the host. These hibernating larvae are called encysts.

Large strongyles, known as bloodworms, can enter the bloodstream as encysts and migrate for six to seven months along the walls of the arteries including the mesenteric artery, the liver, the kidneys, the pancreas, and the intestinal wall causing tissue damage and symptoms of organ dysfunction. They eventually return to the large intestine as young adults. Large strongyles can be responsible for weight loss, a dull coat, poor appetite, a pot belly, itching, fatigue, bloating, colic, diarrhea, and hoof toxicity.

But the most common parasites to infect equines are small strongyles. They are particularly problematic because they burrow into the intestinal lining of the large intestine where they can stay for years. In defence the horse’s body creates inflammation and forms scar tissue around each larvae. The process forms little blood-filled cysts which the larvae can feed off. Small strongyles can therefore cause colic, anemia, weight loss, and mal-absorption of nutrients.

Bear in mind that it is not of benefit for any type of parasite to kill off its host so most horses continue to get sicker rather than die.

Treatment

The treatment of equine parasites is not as simple as we think. Nor is it as easy as shooting a full syringe of any dewormer into your horse’s mouth twice per year. Not only are there different types of parasites but each horse has different levels of resistance – some horses with a high count have no symptoms whatsoever and other horses with hardly any infestation have no resistance at all and show a variety of symptoms. As well, there is much concern about over-medicating horses with chemical de-wormers leading to imbalances in the colon as well as the mutation and resistance of the parasites themselves. And unfortunately, for some horses, especially those with encysts or heavy loads, herbal and homeopathic treatments are not effective enough.

Chemical De-wormers – The Risks

Chemical de-wormers came on the scene in the 1960s to target all species of worms. Only one new de-worming medicine has been introduced in the past 15-20 years and few new ones are expected. In recent years, however, the chemical war on parasites has become less popular for the following reasons:

- Worms, especially small strongyles and roundworms, adaptive creatures that they are, have learned to build resistance. This has no doubt been spurred on by overly-aggressive parasite drug treatments putting selective pressure on worms to mutate. The indiscriminate and repetitive use of chemical de-wormers on horses (especially those horses who may not even be infested), leads to parasitic mutation, and puts the horses at risk for toxic chemical overload and compromised immunity.

- Using chemical dewormers too often (e.g. daily or weekly) or using excessive dosages can contribute to intestinal damage, a change in the colonic ecosystem, a depletion of probiotics, liver and kidney stress, and overall chemical toxicity. Adverse reactions to all chemical de-wormers may include drooling, colic, swellings, weight loss, allergic reactions, and laminitis. Don’t keep repeating or increasing dosages or trying different medications when they are not working. Random treatments used in a parasite laden environment without improving the nutrition will accomplish very little. It is not a relentless war of eradication.

- Be cautious of de-wormers that claim to kill encysted larvae, since in order to do so the drug must chemically alter the intestinal membrane to access the larvae. In sensitive horses this can lead to leaky gut, malnutrition, colic, and weight loss – sometimes extreme.

- Chemical de-wormers often trigger the unaffected encysted larvae to emerge and develop into adult worms as soon as the drug is gone from the horse’s system. These newly developed adult parasites begin to shed eggs immediately and, depending on the time of year, can begin developing into parasites almost immediately.

- Small strongyles that are encysted in the intestinal walls only respond to two different chemicals: moxidectin and fenbendazole. If you use other less effective dewormers on a horse with an extreme overload of small strongyle encysts a dangerous process called emergence (Larval Cyathostomosis) can happen. Encysts in the intestinal wall will emerge into the colon all at once in an attempt to replace the non-encysted ones that have been killed by the de-wormer. This onslaught can cause colic, weight loss, diarrhea, and swelling.

- Only 30% of the horses in any herd (usually those with the lowest resistance) are carrying the majority of the parasite load. This means that nearly 70% of our horses are subjected to excessive and unnecessary chemicals on a regular basis.

- Chemical parasite control measures shift our focus away from more natural parasite preventions such as controlling environmental contamination and keeping our horses intestinal health resistant to infections of all kinds, including parasites.

Chemical Dewormers – When to Use

- Chemical dewormers are very much still a necessity for horses with a heavy parasite load, those who have not been treated on a regular basis, those horses who are primarily out on grass, and those horses who have encysts, of which there are many. Most horses on dry lots who are eating hay have the least number of parasites and can be more easily managed.

- Always make use of fecal parasite tests before deworming to determine whether or not your horse even has an overload of parasites. Bear in mind that a fecal parasite count will not indicate the presence of encysted parasites however I do find that those horses with high levels of encysted parasites will often (but not always) have a high load of shedding parasites as well.

- When using any kind of chemical dewormers be sure to protect the colon and liver from chemical trauma and toxicity by combining with the following natural program:

- Pro-Colon pre and probiotic (live bacteria) – One 30-day course once or twice per year to re-establish healthy levels of friendly bacteria.

- Gastricol (homeopathic remedy) – Give one dose twice daily 3 days before the de-worming and 7-10 days after the last chemical dose.

- Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) – 2 tsp daily (5,000 mg) for 14-21 days.

Chemical Dewormers vs Herbal Dewormers

I have seen the fecal tests of many, many horses who were either not dewormed at all or were given a variety of different dewormers including chemicals, diatomaceous earth, and various herbs. I wish it were not so but most of those horses who had not been given chemical dewormers at any time, or were given only herbal remedies had the highest loads. And those same horses with moderate to high counts or encysts were not able to reduce their fecal count with natural remedies alone.

That said, we can still reduce the amount, frequency, and potential damage of chemical de-wormers by ensuring good nutrition and using effective natural remedies. Parasite resistance and prevention is very dependent on optimum digestion, a healthy hindgut, and a strong intestinal immune system.

Natural Parasite Prevention

Poor resistance to parasites is caused by poor feeding practices, inadequate nutrition, lack of exercise, stress, and a toxic colon. Horses in poor condition with digestive problems are good hosts. The intestinal environment created by high sugar-carbohydrate diets from excess grass or grain is favoured by disease causing-pathogens and parasites. High sugar fermentation produces a highly acidic environment that favours and encourages the proliferation of bacteria, yeast, and parasites.

Horses are not meant to have a sterile intestinal system. A healthy ecosystem relies on a balance of microorganisms including bacteria, yeast, and some parasites. If horses are never exposed to parasites, they will never build natural immunity and stronger resistance.

Parasite Prevention Practices

- Feed a low sugar diet.

- Keep grass grazing, grains, and commercial feeds to a minimum.

- Feed your horses frequently. Small frequent meals or slow feeders encourage strong digestion and prevent stress, ulcers, and poor resistance to parasites. Don’t let your horses stand idle for long periods of time without anything to eat.

- Ensure regular exercise – exercise is critical for keeping horses healthy.

- If possible, allow your horses free forage so that they choose different plant medicines that they are drawn toward.

- Build resistance with natural and herbal remedies.

Riva’s Remedies

Feed the following program for 4-6 weeks – twice per year.

Pro-Colon pre and probiotics

This is a blend of live bacteria formulated specifically for horses to promote a healthy intestinal immune system, protect the eco-system, and support nutrient absorption.

Para+Plus herbal blend

Contains dandelion, elecampane, gentian, kelp, sage, thyme, Vervain blue, wormwood, and yellow dock – ¼ cup daily. This blend is formulated to support those horses affected by parasites, bacteria, yeast, and fungus. It is also a natural liver detoxifier and promotes healthy immunity.

Vinegar, white or apple cider – 2-3 Tbsp daily

Vinegar helps to acidify the intestinal system, discourages parasites and encysts, acts as a natural antibiotic, and improves digestion. Don’t use vinegar every day for indefinite periods of time.

Healthy Horses

By understanding parasites, as well as the various ways to build resistance, the prevention and treatment programs for horses with parasite loads – low or high – can be a lot more effective than what many of us have in place right now.

The naturally healthy horse with a high level of resistance is a horse with strong immunity, efficient digestion, suitable diets, adequate levels of exercise or free forage, regular cleanses, and well-selected remedies, including the smart use of chemical dewormers.

Acupressure for Shelter Animals

Editor’s Note: This article has been sourced via Tallgrass Animal Acupressure Institute.

Animal shelters are tough places no matter how hard staff and volunteers work to make them comfortable. Being in a shelter is terribly disorienting for a dog or cat, and in their confusion and fear, they may act out or retreat into themselves. Acupressure-massage is one way to offer these animals emotional and physical comfort and care until they are adopted into their forever homes.

Before you Start, Calm and Center Yourself

If you work or volunteer at an animal shelter, or want to try this technique on a newly-adopted dog or cat or other fearful and disoriented animal, be sure to start with ourself. Working at a shelter is stressful, but you have to be present, calm, and thinking about what you want the dog or cat to experience during the session. For example, you could set an intention that the session will be loving, comforting and calming; every animal in a shelter needs this, no matter what.

To being, the acupoint referred to as Large Intestine (LI4) can help you calm and center yourself. Located in the webbing between your thumb and forefinger, this point is known to help release pressure in the face, mouth, and head. It’s used to mitigate migraines, dental pain, and feelings of stress, and to promote a sense of calm.

Hold the webbing between the thumb and forefinger of one hand between the thumb and pointer finger of the opposite hand, with the thumb on top and the finger below the webbing. While holding that point, think about what you want the animal to receive during his or her session. Slowly take three deep breaths. Then change hands and repeat the procedure.

Calming Acupressure-Massage Session for Dogs and Cats

Once you feel present and focused, you are ready to begin the session. Animals know immediately when you are thinking about something else, like what you need to buy at the store on your way home. The session will be much more effective if you are grounded, caring, and present.

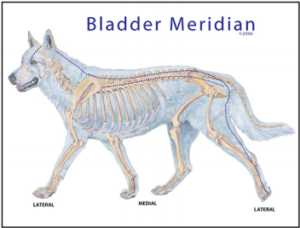

Start by using the heel of your hand to slowly stroke down the animal’s body just to the side of his midline and spine from head to hind paw, following the Bladder Meridian Chart. Trace the meridian three times on each side of the animal’s body. This tells the bod or cat you are doing something other than petting him. Your intention is to be comforting and help him feel calm.

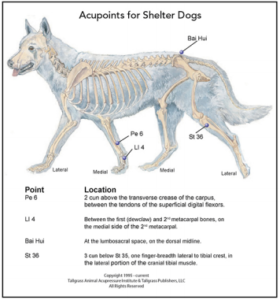

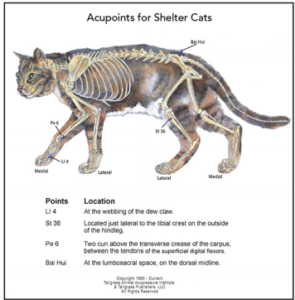

Once you have completed tracing the Bladder Meridian three times on each side of the animal’s body, you are ready to offer specific acupressure points to help restore a feeling of well-being (see charts below for the names and locations of these points). The acupressure points selected for animals in a shelter environment support general health, reduce fear, boost the spirit, and promote a sense of courage and well-being.

Acupressure Point Techniques

While performing acupressure point work. always have both hands on the animal at the same time. One hand is doing the point work while the other rests gently and comfortably somewhere on the dog or cat’s body. The resting hand can feel any reactions the animal has to the point work, while offering grounding and comfort.

If you are unfamiliar with acupressure, you need to know that there are two basic techniques for stimulating acupoints – the Thumb Technique and the Two-Finger Technique. Both are considered direct pressure techniques, called an An Fa in Chinese. There’s no need to press hard because the meridians and acupoints are just beneath the surface of the skin. In fact, gentler is better, so you won’t obstruct the flow of chi.

Thumb Technique – Gently place the soft tip of your thumb on the acupoint and count slowly to 20, then move to the next point. The

Thumb Technique – Gently place the soft tip of your thumb on the acupoint and count slowly to 20, then move to the next point. The

Thumb Technique works best on larger dogs and on a medium-sized dog’s trunk, neck, and larger muscle masses.- Two-Finger Technique – Place your middle finger on top of your index finger to

create a little tent. Then lightly put the soft tip of your index finger on the acupoint and count slowly to 20. This technique is good for point work on small dogs or cats, and for the lower extremities on medium-sized to large dogs.

create a little tent. Then lightly put the soft tip of your index finger on the acupoint and count slowly to 20. This technique is good for point work on small dogs or cats, and for the lower extremities on medium-sized to large dogs.

When you have completed the point work, trace the Bladder Meridian three times on each side of the animal just as you did at the beginning of the session. This gives the acupressure-massage session a finishing touch; it’s like smoothing a bedspread and tidying up the energy.

Soothing Ah-Shi points with Tui Na

Editor’s Note: This article has been sourced via Tallgrass Animal Acupressure Institute.

In Part One of this two-part series, we went over the nature of Ah-Shi points. We discussed how the muscle tissues tighten and become knotted. This can occur spontaneously due to physical or emotional stress, injury or disease. The result is the same: the tissues shut down, not allowing blood and chi to flow. The animal then experiences pain, which leads to restricted movement.

When Ah-Shi points and the surrounding tissue are not addressed quickly, the animal tends to compensate to avoid pain. This leads to the horse’s, dog’s, or cat’s entire body becoming physically compromised. What may have begun as a minor tightness can snowball into a major lameness. Acupressure-massage, called Tui-Na in Chinese, is a highly effective hands-on bodywork modality that is known to resolve Ah-Shi points and the surrounding tissues.

Tui Na

Tui Na is one of the five main branches of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) along with diet, chi gong, herbs, and acupuncture. It is considered the original Chinese meridian massage. Tui Na is pronounced “Tway” with a long “a” sound and “Nah.” Translated, Tui Na means “push – grasp.” It has been continuously practiced in China for both humans and animals since 2700 B.C. Over time, these techniques followed the Silk Road to the Middle East and on up through Europe to Northern Europe.

Tui Na regulates meridians by promoting the circulation of chi, blood, and other vital substances. This, in turn, provides the energetic and nutrient nourishment necessary for the internal organs to function properly. When there’s a harmonious flow of vital substances, all the bodily tissues are nourished, and Ah-Shi points are less likely to form. However, if they do, they can be easily resolved with these hands-on techniques that have been used for centuries.

Tui Na Techniques

The first Tui Na technique is direct pressure, called An Fa. Begin pressing very lightly because the point can really hurt. Come away from the point and then press ever so slightly more into the point using the soft tip of your thumb, knuckle, or the heel of your hand. There are many variations of how to apply An Fa including crossed-hands or an elbow on larger equine muscle masses.

Tui Fa is a “pushing” technique that is used to trace a specific meridian that is blocked along its path and possibly where an Ah-Shi point has formed. The hand movement needs to be relaxed, smooth and consistently sliding along the meridian. Sliding up and back using the soft tip of the thumb, three fingers, or the heel of the hand removes obstructions and can invigorate the flow of chi and blood.

There are a huge number of Tui Na techniques to enhance the effectiveness of an acupressure-massage session that is best learned by taking hands-on training courses. The general purpose of using Tui Na techniques is to invigorate the harmonious flow of vital substances throughout the animal’s body to help resolve painful Ah-Shi points.

Feed Cranberries to Horses

Editor’s Note: This article has been sourced via Riva’s Remedies.

I’m always looking for new foods that horses might like to provide them with variety and extra nutrition. Turns out that raw organic cranberries are the new face around here – they gobble them right up even with the tart taste. Cranberries are rich in Manganese, Vitamin C, Vitamin E, fibre, and anti-oxidants. They are a natural anti-inflammatory and antibiotic, and are beneficial for the immune system and heart. Just add 1/4 cup to their breakfast.

Winter Laminitis

The Don’ts of Caring for a Laminitic Horse

- Don’t put a laminitic horse on pasture – fresh grass is very high in sugar, especially in the spring, summer and the hottest part of the day.

- Don’t feed oats, barley, corn, COB, grains or any other commercial grain feeds including extruded feeds – these (as well as grass) are all high in sugar and non-structural carbohydrates which increase blood sugar, insulin levels and cecal acids and toxins – all major causes of lamina inflammation.

- Don’t feed high fat feeds or added oils. While current popular opinion promotes feeding horses poor quality fats for “cool” energy and for lowering the glycemic index of forage and grain, fats and oils congest the liver and lymph system, slow down digestive transit time, impede nutrient absorption, contribute to leaky gut, have no nutritional value and increase cortisol levels which elevates blood sugar.

- Don’t feed alfalfa. While the high protein levels in alfalfa will lower the glycemic index and stabilize blood sugar in SOME horses, excess alfalfa will exacerbate laminitic symptoms in most horses by contributing to a leaky gut and/or by increasing the deposition of acids into the hoof joints.

- Don’t soak your hay for longer than two to three weeks – any longer than that could increase hunger and stress levels as the sugar and/or protein levels may become deficient. Any hay that needs to be soaked long-term to maintain weight or soundness is not the right hay.

- Don’t starve the overweight laminitic/metabolic horse – this creates stress causing unbalanced insulin levels, increased cortisol production, poor immunity and an increase in hoof inflammation. Feed small amounts of forage frequently by using slow feeders.

- Don’t confine a laminitic horse no matter how sore they are – horses need movement and exercise to improve circulation and deliver nutrients to toxic and damaged hoof tissues. Let the sore horse decide how much movement he/she needs. Metabolic horses with laminitis need exercise to regulate blood sugar levels and to reverse their condition.

- Don’t use glucosamine long-term, if at all – glucosamine is a type of sugar that strains the liver and depresses insulin production in sugar sensitive, overweight and/or metabolic horses.

- Don’t accept hoof pathologies as normal (no matter what breed): flaring walls, bell-shaped hooves, cracking, splitting, soft soles, flat soles, long toes, high heels, contracted heels and/or under-run heels are all abnormal and can be fixed with a professional barefoot trim, exercise and a good diet.

- Don’t always accept the label of “navicular” – this is an over-used diagnosis to explain unexplained symptoms. Many cases of so-called navicular are actually sub-clinical laminitis.

- Don’t listen to well-meaning people who tell you that your horse won’t recover – they are misinformed.

The Do’s of Caring for a Laminitic Horse

- Do feed horses a high fibre diet (e.g. hay, beet pulp, soybean hulls, flax seeds, chia seeds, hemp seeds, wheat bran, wheat germ) – fibre detoxifies the liver and hindgut, regulates appetite, lowers the glycemic index of all feeds and encourages weight loss.

- Do use slow feeders to lower stress levels, ease digestion and provide forage 24/7.

- Do treat horses for a leaky gut if present – hindgut bacteria, acids and toxins are a major cause of laminitis. Use Pro-Colon probiotics, Pro-Dygest, Para+Plus and/or Vitamin B12.

- Do treat horses for parasites – parasitic toxins exacerbate hoof inflammation and/or laminitis.

- Do ensure a proper barefoot trim with good hoof mechanism. Note: a pasture trim is not a barefoot trim. A pasture trim is done to nail a shoe on, a barefoot trim is done to maximize proper hoof growth and performance. Educate yourself on different trimming methods.

- Do also educate yourself on sub-clinical laminitis – this is a type of laminitis that shows no clinical signs of separation, digital pulse or hoof tenderness. It is a common cause of hoof soreness and is absolutely under-diagnosed!

- Do know that the most common hoof nutrient deficiencies are selenium, silica and sulphur – all minerals which strengthen hoof wall, lamina and joint capsules.

- Do also know that rotated hooves will correct themselves if the horse is fed an appropriate diet with the right supplements and is trimmed with a professional barefoot trim. Marijke has guided hundreds of laminitic horses in varying stages to 100% soundness – many of these horses were considered untreatable.

- Do use boots and/or casts to relieve pain and encourage movement in the acute stages.

- Do practice prevention – good food, good trims, good exercise!

- Do read Healing Horses Their Way for an extensive resource of information on laminitis…and much more.

Happy Hooves, Happy Horses!